-40%

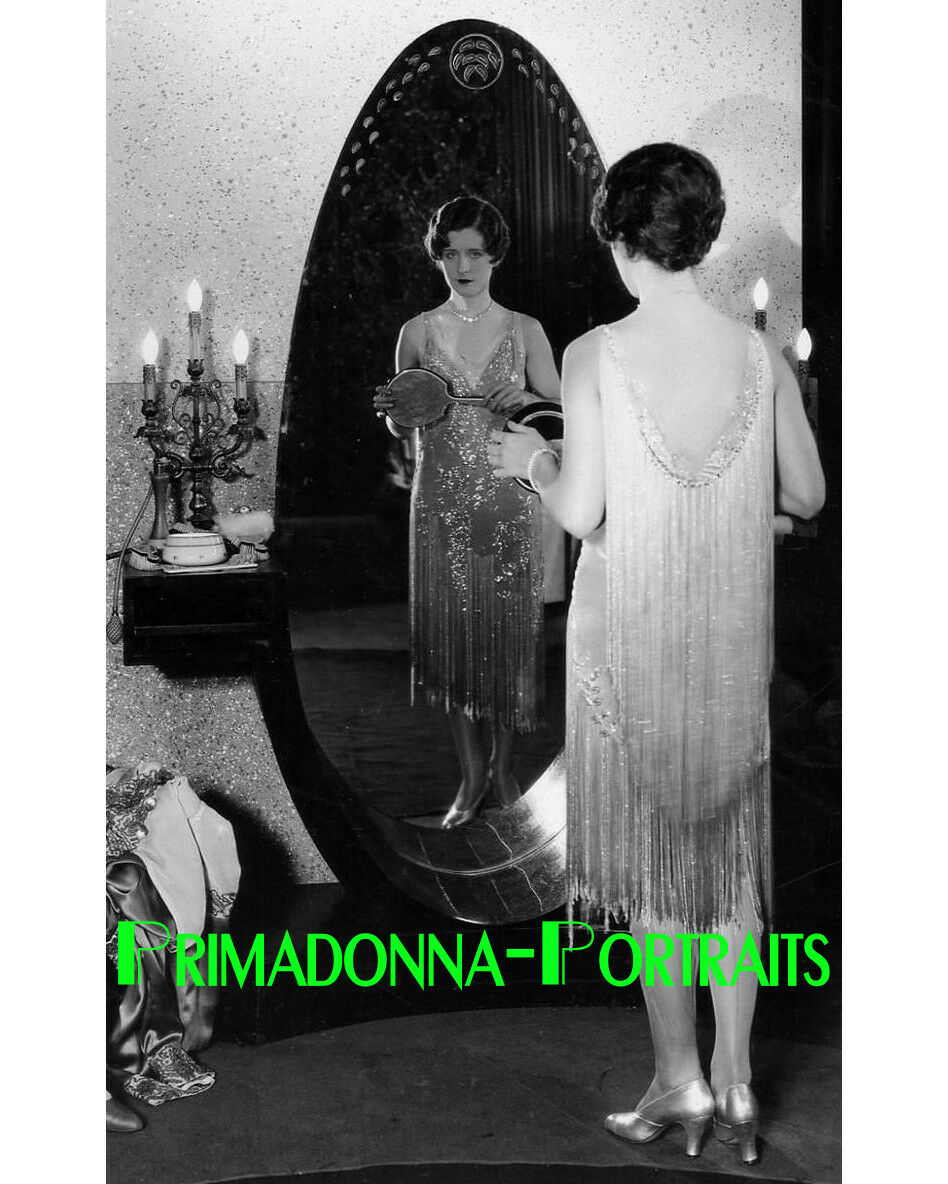

Early Silent Film Pioneer Anita Stewart Large Original Edwin Bower Hesser Photo

$ 2.61

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

ITEM: This is a c. early 1920s vintage and original large format photograph of pioneering early silent film actress Anita Stewart. One of the most popular stars of the 1910s, Stewart also started her own production company, Stewart Productions, with Louis B. Mayer and began to produce her own feature films. Stewart is the picture of early 20th century glamour and sensual beauty with her brown hair wavy and wild around her shoulders and her gown loose around her shoulders and chest, exposing just enough of her bare skin to be tantalizing but not vulgar. This exceptional portrait is by Edwin Bower Hesser.Photograph measures 10.25" x 13.25" without margins, as created, on a matte double weight paper stock with the photographer's ink stamp on verso.

Guaranteed to be 100% vintage and original from Grapefruit Moon Gallery.

More about Anita Stewart:

Anita Stewart began her career as an actress at the Vitagraph Company in 1911, and rose to become one of the most popular stars of the teens. In 1918 she started Anita Stewart Productions, in partnership with Louis B. Mayer, and began to produce her own feature films for First National Exhibitors Circuit. Anita Stewart Productions produced seventeen feature films between 1918 and 1922. After concluding her association with Mayer, Stewart accepted an offer from William Randolph Hearst to appear in Cosmopolitan Productions. She continued to make films with Fox, Columbia, and lesser studios through the end of the silent era, appearing in her last feature in 1938.

Born Anna Marie Stewart in Brooklyn in 1895, she was the middle of three siblings. Her older sister Lucille Lee and younger brother George also became film actors. Lucille Lee Stewart was the first to work in films, starting with the Biograph Company in 1910, and shortly thereafter moving to the Vitagraph Company, where she met and married director Ralph Ince, younger brother of Thomas Ince. Anna Marie Stewart was a high school student who had done a little modeling when Ralph Ince telephoned to say he needed some extra juveniles for a film. After her start in early 1911, sixteen-year-old Anna quickly became a Vitagraph regular, appearing in vehicles that featured the “Vitagraph Girl,” lead actress Florence Turner. Within a year Anna was herself given lead roles, receiving popular recognition for The Wood Violet (1912). After a typographer’s error changed her name from “Anna” to “Anita” in publicity for The Song Bird of the North (1913), she decided she liked it, and kept “Anita Stewart” as her professional name (Bodeen 120). Her career was assured when she became a hit in the lead role of Vitagraph’s second multireel feature, A Million Bid (1914).

Soon, Stewart was being promoted as “America’s daintiest actress,” and her image was featured on sheet music, souvenir plates, silver spoons, and a collection of paper dolls published in Ladies’ World Magazine. In 1915, Munsey’s Magazine noted that, though she had appeared in but two features and a serial and had never appeared on the theatrical stage, “her face is perhaps familiar to as wide a circle as Maude Adams’s” (88).

Stewart’s career continued at Vitagraph, and with only a few exceptions she was given leading roles in each film. The great majority of her films were directed by brother-in-law Ralph Ince, and she quite enjoyed the familial atmosphere of the company. But beginning in 1916, Vitagraph began to assign other directors to her films, one of which, The Glory of Yolanda (1917), was directed by frequent scenarist Marguerite Bertsch. Still, Stewart did not feel that all of her new directors were equally competent, and during production of two films directed by Wilfrid North, she effectively went out on strike, leaving the productions unfinished while she claimed to be convalescing from an auto accident. The same year, 1917, Anita Stewart quietly married costar Rudolph Cameron, although the marriage was kept secret from her public for over a year (Bodeen 122–123).

Among her thousands of devoted admirers was a newspaper boy named Toby who has been described as a hunchbacked dwarf. Toby took it as his duty to promote the actress to virtually anyone who would listen. “Toby was one of my most ardent fans,” Anita Stewart later wrote. “I never knew his last name. He used to beg pictures from my secretary and gave them away at the opening of the horse show and any large social gathering. Toby met Mr. [Louis B.] Mayer at the train each time he came to New York, (and) he introduced me to him” (“Anita Stewart” n.p. Bosley Crowther Papers; Crowther 1960, 53–81). Mayer, at the time of his first meeting with Stewart, was a young Massachusetts theatre owner who had made a small fortune as a regional film distributor by cornering the New England distribution rights to The Birth of a Nation (1915). Now he wanted to produce films himself; but in order to secure backing and critical attention, he needed to recruit a star.

Mayer knew that the First National Exhibitors Circuit, which had just signed Charlie Chaplin, was looking for established stars who wished to produce their own independent films, so he approached Stewart about forming her own company: Anita Stewart Productions. Why did she accept his offer? “I was completely happy at the Vitagraph,” Stewart wrote many years later, ignoring her battle over her directors, “and have often felt that I made my best pictures there, but Mr. Mayer promised me better parts, better directors, more money—really the moon, and at the time I was anxious to come to California” (“Anita Stewart,” n.p. Bosley Crowther Papers; Crowther 1960, 53-81). Husband Rudolph Cameron became her business manager, and along with Stewart, was promised a cut of the company profits. In reality, however, Mayer had little experience to back up the promises he had made. While Anita Stewart at twenty-three was a seven-year veteran of the industry, having worked her way up through dozens of shorts to the first rank of Vitagraph feature stars, Mayer’s only previous production experience at the time appears to have been as a junior executive on one serial.

Anita Stewart Productions was launched with great fanfare and wide publicity, but in hindsight, it was launched too soon. Before the actress, now producer, could start her new venture, the Vitagraph Company slapped Anita Stewart Productions with a lawsuit, claiming that the star was still under exclusive Vitagraph contract at the time that she signed with Mayer. The suit was decided in favor of Vitagraph, a ruling cited in later cases involving actor contracts (Bodeen 123; Eyman 2005, 56). According to Stewart, as a result of this suit she lost the percentage of profits she was entitled to have received from her Vitagraph films (“Anita Stewart” n. pag. Bosley Crowther Papers). However, while Mayer paid ,000 to Vitagraph as part of the settlement, Anita Stewart Productions received two unfinished Vitagraph productions that were subsequently completed by Stewart and released by First National (Bodeen 123; Slide 1976, 88).

Stewart’s first new feature for her own company, Virtuous Wives (1918), was directed by George Loane Tucker and filmed at New York studio space rented from Vitagraph, no less. For Stewart, however, it was not a happy shoot. Supporting actress Hedda Hopper, providing her own costumes, reputedly spent her entire salary of ,000 on custom gowns that Stewart felt upstaged her own wardrobe. Consequently, the two women refused to talk to each other on the set, beginning a feud that reportedly lasted some twenty years (Bodeen 1976, 124). Released at the end of December 1918, however, the film was a success. Following this production, Stewart and Mayer and their respective families all moved to Los Angeles, where Anita Stewart Productions settled into its new home in rented space on the Selig Polyscope Company lot (Bodeen 125; Kingsley 1919, III,1).

In a Los Angeles Times profile from January 1919, Anita Stewart is quoted: “It’s a great responsibility, being a producer, you’re honestly rather afraid to get to the top. There are so many to push or pull you off.” In the same interview, Stewart talked about stories she would like to produce in the future (Kingsley 1919, III,1). She wanted to film David Graham Phillips’s sensational novel about a woman working her way out of prostitution. That novel, Susan Lennox: Her Fall and Rise, would come to film much later, in 1931, as a pre-Code “Talkie” with Greta Garbo. Another idea was Theodore Dreiser’s sexually provocative Sister Carrie, a novel not adapted for film until 1952. But Stewart’s choice of stories would ultimately place her in conflict with her partner, Louis B. Mayer. According to Mayer biographer Scott Eyman, the producer preferred stories that could be “insanely moralistic” (2005, 58). Mayer once indicated to screenwriter Frances Marion that he only wished to make pictures that his two young girls could see (Beauchamp 1997, 145). The sort of mature stories that appealed to Anita Stewart were out of the question.

Much remains to be learned about the extent to which the actress-producer was involved in the decision-making at Anita Stewart Productions. Unfortunately, the prints of the films themselves do not give us any clues, and on extant prints examined by this contributor, Louis B. Mayer receives screen credit as presenter. But while Mayer was anxious to learn production, the crew thought he was a novice, and he was not on the set on a daily basis (Eyman 2005, 58). In contrast, since the actress-producer was the sole partner in Anita Stewart Productions, consistently present on the set of her films, it seems logical to conclude that Stewart was in position to make the daily production decisions that might be required of her as well as other creative decisions. An accomplished pianist, she wrote both music and lyrics for songs published in conjunction with the release of the pictures she produced in 1919, A Midnight Romance, Mary Regan, and In Old Kentucky (see Wlaschin 305, 309). From the comprehensive 1919 Los Angeles Times interview with Grace Kingsley, it is clear that Stewart thought of herself as a producer of her company’s product (III, 1). In this role she might, then, have made the decision to hire director Lois Weber, an engagement that warranted the Los Angeles Times news flash “Anita Stewart Engages Noted Woman Director” (Kingsley 1918, III,1). For their first production together, Weber wrote her own adaptation of a romantic mystery by Marion Orth. The film, A Midnight Romance (1919), survives in a partial print at the Library of Congress. But the title represents Weber at her most unapologetically commercial. Their second and final collaboration came with Mary Regan (1919), an adaptation of the popular novel by the same name about the daughter of a thief who tries to protect and reform the men she loves. After her brief association with Weber, Anita Stewart was directed by top directors of the day, including Marshall Neillan, Edward José, Edwin Carewe, and John Stahl. But it was Louis B. Mayer who prevailed in the choice of stories, a fact that Stewart grew to resent. According to historian DeWitt Bodeen, when her contract concluded in 1922, Stewart refused Mayer’s offered renewal, and went her own way, closing the doors on Anita Stewart Productions (125).

Some months later Stewart was shocked and saddened when her former director and brother-in-law, Ralph Ince, was indicted for the brutal beating, during an argument, of her own younger brother, actor George Stewart. George suffered brain damage, and remained an invalid for the rest of his life, with Anita eventually taking over his care. She returned to the screen one year after the release of her last Anita Stewart production in The Love Piker (1923), a film written and produced by Marion for the West Coast division of William Randolph Hearst’s Cosmopolitan Productions. The last of three Cosmopolitan pictures was Never the Twain Shall Meet (1925), a South Seas adventure directed by Maurice Tourneur, which Stewart remembered as her personal favorite (Bodeen 126).

After this, her career quickly devolved into leading roles in lower budget productions for a succession of Poverty Row studios. Most of these were action-adventure films, including a remake of the Nell Shipman role in Baree, Son of Kazan (1925) and the Mascot serial Isle of Sunken Gold (1927). Her last leading role was in Romance of a Rogue (1928), which starred H. B. Warner and was also the last directing credit received by prolific actor-director King Baggot. Following her retirement from the screen and her 1928 divorce from Rudolph Cameron, Anita Stewart married George Converse, a New York sportsman and the heir of a United States Steel president. The couple bought a home in Beverly Hills. Stewart made several singing appearances, both in person and on the radio, and appeared in a cameo as herself in the Universal musical short The Hollywood Handicap (1932). Stewart and her second husband were divorced in 1946 (Bodeen 126–127).

In 1935 Anita Stewart authored a mystery novel, The Devil’s Toy, a strange tale in which a young stage actress comes under suspicion for a series of murders, apparent poisonings, all of which take place in the theatre. Stewart fashioned a character in her novel after the ardent fan who had introduced her to Louis B. Mayer eighteen years earlier. In her story, Toby, the hunchbacked dwarf, is the “genius of theatrical lighting” who idolizes the young actress from his position at the controls of a spotlight that follows her every movement on stage. In the surprise ending, Toby is revealed to be behind the murders, accomplished with a death ray he has invented and hidden inside one of his spotlights. When he mistakenly believes he has killed the heroine, Alice, by accident, he destroys his invention and takes his own life, thinking that in death he will at last be united with the woman he worships. Anita Stewart died of heart failure in Beverly Hills on May 4, 1961.

Biography By: Hugh Neely, Women Film Pioneers Project

More about Edwin Bower Hesser:

Hesser belonged to the generation of photographers who saw the marriage of image and performance as the future of the art. Born in New Jersey and apprenticed in photography in New York City, Hesser became smitten with the potentials of the art form.

Prior to World War I he toured northeastern theaters with J. Townsend Russell in a series of "picture readings" illustrating Longfellow's Tales of a Wayside Inn. Townsend recited the poems accompanied by a string orchestra while illustrative photographs were projected on the screen. In 1913, Hesser introduced Roald Admundsen, the first man to reach the south pole, to New York audiences, presenting motion pictures to illustrate the trek. On February 3, 1915, using family money, he incorporated the Hesser Motion Picture Corporation with a capitalization of ,000. Later in the year, he was in Atlanta opening the Hesser School For Motion Picture Acting.

With America's entry into World War I, Hesser joined the U. S. Army Signal corps with the rank of Captain and oversaw land photography. While in the service a scenario composed by Hesser, "The Freedom of the World," was made in 1918 into a semi-documentary feature film by Goldwyn. After the armistice, Hesser decommissioned, set up a photographic studio in Manhattan employing as his assistant a talented Italian, Nino Vayana, to oversee production. He was drawn to the world of movies and worked as a contract photographer for numbers of silent stars based in New York, particularly Norma Talmadge, Irene Castle, and Marion Davies. A fire in 1922 destroyed his production facilities and his stock of early negatives. He began to make regular trips to the West Coast for photographic sessions with Hollywood stars, and finally moved his base of operations to there.

By 1923 he realized that the real money in photography lay in periodical publication, not in the service of film publicity offices or stage PR men. He saw particular opportunity in the subject which the 1920s stage explored with great daring, but the screen, even in pre-code days, could not pursue: female undress. Throughout the late 1920s, he published Edwin Bower Hesser's Arts Monthly, and other titles, exploiting the association betweens art and nudity, and sold it to an anonymous readership of "art students." The magazine published work by Alfred Cheney Johnston, John De Mirjian, George DeBarron, and Strand Studio.

Hesser's exploration of the netherworld of publishing brought him in contact with the Hollywood underworld. In 1928 he was arrested for suspicion of narcotics peddling, battery, and impersonating a police officer in connection with the death of starlet Helen St. Clair Evans, who was murdered by her husband Arthur. He was released, but the Depression shut down Hesser's successful exercise in niche publishing.

Fortunately for Hesser, his experiments with color photographic processes and his experience with mass reproduction of imagery made him attractive in the eyes of the New York Times, who hired him as a technician. Later in the decade he returned to California. Hesser continued to practice photography until the late 1940s placing occasional pieces with magazines. His photographic archive is stored in the special collections department of UCLA library. David S. Shields/ALS

Specialty:

Hesser was one of the few portraitist who regularly depicted sitters head on. His penchant for back-lighting so that hair seem lined with light, gave certain of his 1920s sitters a halo or aura. Hesser's plein air nudes of showgirls in natural light became the academic standard for art photographers in the 1920s, while his portraits of movie actresses and stage stars were greatly influential images of glamour from 1925 to 1930. Also an expert at landscape photography, Hesser combined these two skills--often photographing nudes in parks and glades.

Possessed of an inquiring and entrepreneurial mind, he developed and patented a color process, "Hessecolor," that intrigued mass circulation publishers during the 1930s, but did not prevail in the marketplace.

Biography By: Dr. David S. Shields, McClintock Professor, University of South Carolina,

Photography & The American Stage | The Visual Culture Of American Theater 1865-1965